When people mention the word 'ocean' many think of the endless blue that touches the sky on the horizon. However, oceanic expanses are not so monotonous. In addition to the usual islands, peninsulas and coral reefs that we used to see at the ocean expanses, there are some ocean landscapes that are simply unique in the world.

1. Meeting Place of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea at Eleuthera Island, Bahamas

Eleuthera is one of several islands that lies within the archipelago in The Bahamas, about 80km (50mi) east of the capital city Nassau. It is long – about 180km (112mi) – and thin - only about 1.6 km (1mi) wide in places. The light blue waters of the shallow Caribbean Sea on one side of the island stand out in stark contrast to the deep blue of the Atlantic Ocean thousands of feet in depth. One of the best places to see this extraordinary juxtaposition is at the Glass Window Bridge.

The Glass Window Bridge is about two miles east of Upper Bogue and joins Gregory Town and Lower Bogue at the narrowest point on the island. It is one of the few places on earth where you can compare the rich blue waters of the Atlantic Ocean on one side of the road and the calm turquoise-green waters of the Exuma Sound (Caribbean Sea) on the other side, separated by a strip of rock just 30 feet (10m) wide.

Over the natural rock bridge, a concrete bridge has been built that connects the northern and southern points of Eleuthera by a paved road. The Glass Window Bridge is one of the most visited places in the island.

For centuries, there was a natural stone bridge connection between north and south Eleuthera. Then in the 1940's, several hurricanes combined to destroy the land bridge and the concrete bridge was built as replacement. For decades, this bridge was kept functional by periodic repairs, but in 1992 and 1999 hurricane caused significant damage to the bridge. After the 1999 Hurricane Floyd, practically nothing of the original Glass Window Bridge remained. Although the bridge was repaired and Queen's Highway re-connected within a few months, the geography of Eleuthera was changed forever. Even after a decade, workers stay busy reinforcing the shoreline in order to re-pave the severely eroded asphalt.

One should take great care when visiting the Glass Window Bridge and the surrounding cliff areas. Rogue waves have been known to arrive unexpectedly and wash over the bridge and nearby cliffs. Since there are no immediate reefs along the ocean side to break up these rogue waves as they arrive, the waves can hit with great force and have been known to not only wash people out into the ocean, but vehicles as well.

Land is undergoing continuous erosion from the force of water that pounds from towering heights. On the left, approaching the bridge from the south, is a blow hole that spews water fantastically high, hinting at the power of the water beneath.

2. Meeting Place of the Baltic and North Sea, Denmark/Sweden

In the resort town of Skagen you can watch an amazing natural phenomenon. This city is the northernmost point of Denmark, where the Baltic and North Seas meet. The two opposing tides in this place can not merge because they have different densities. The area where the Baltic and the North Sea come into contact is quite shallow and so the contact face is relatively small. There is of course some mixing but it is quite minimal due to the difference of the density.

It is also helped by the fact that the Baltic is not tidal which keeps most of its water within the Baltic basin and this water is constantly being reduced in salinity by the rivers which drain into the Baltic. Were it not for that small opening into the North Sea the Baltic would be a giant fresh water lake. The contact area is a great sight to witness.

3. Horizontal Falls, Australia

The Horizontal Falls or Horizontal Waterfalls (nicknamed the "Horries") is the name given to a natural phenomenon on the coast of the Kimberley region in Western Australia.

Despite their name, the Horizontal Falls are a fast-moving tidal flow through two narrow, closely aligned gorges of the McLarty Range, located in Talbot Bay. The direction of the flow reverses with each change of tide. As tides in the Kimberley can reach 10 metres (33 ft), a peak tide gives rise to a significant difference in the sea level on either side of each gorge.

The northern, most seaward gorge is 20 metres (66 ft) wide and the southern, more inland gorge is 12 metres (40 ft). Above each of the gorges are natural reservoirs between six and eight kilometres (4-5 mi) long which fill and empty with seawater through the gorge openings. The inner gorge is also partly fed by fresh water from Poulton Creek.

4. The Deep Channel at the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system. It is composed of nearly 3,000 individual reefs and 920 islands stretching for over 2,650kilometres (1,620mi) over an area of approximately 345,000 square kilometres (133,100sqmi). The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, Australia.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's biggest single structure made by living organisms and can be seen from outer space. The reef structure is composed of and built by billions of tiny organisms, known as coral polyps. It supports an incredible diversity of life and was declared a World Heritage Site in 1981. It is one of the seven natural wonders of the world.

The Deep underwater channel from pictures above, separates Hook Reef from Hardy Reef, smaller reefs that belongs to Great Barrier Reef. It is often photographed from an airplanes and is a significant location for scuba divers.

5. 'Underwater Waterfall', Mauritius

Mauritius is an island nation officially called the Republic of Mauritius, or in French, République de Maurice, located in the Indian Ocean about 2,000 km (1,240mi) off the southeast coast of the African continent. A fascinating illusion can be found at the Southwestern tip of the island. When seen from the air, a runoff of sand and silt deposits makes the illusion of an underwater waterfall. The visually deceiving impression is absolutely breathtaking when seen from aerial shots. In fact, the illusion can even be seen on Google Maps.

Satellite views are dramatic, as an underwater current seemingly appears off the coastline of this tropical heaven. Viewed from other perspectives, the ocean appears to be a spectacular gamut of greens, blues, and whites, creating the false impression that it plummets down just like a raging waterfall. Causing the visual magic here is the sand, which is the fair-colored part of the water. The current caused by waves smashing against that specific part of the island causes the sand to be dispersed in a natural, waterfall-like manner of the receding waves’ downward pull. In a manner of speaking, it is in fact an underwater waterfall, but more akin to an hourglass, rather than a typical cascading water.

6. The Great Blue Hole, Belize

The Great Blue Hole is a large submarine sinkhole off the coast of Belize. It lies near the center of Lighthouse Reef, a small atoll 70 km (43 mi) from the mainland and Belize City. The hole is circular in shape, over 300 m (984 ft) across and 124 m (407 ft) deep. The Great Blue Hole is a part of the larger Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, a World Heritage Site of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

This is a popular spot amongst recreational scuba divers, who are lured by the opportunity to dive in crystal-clear water and meet several species of fish, including giant groupers, nurse sharks and several types of reef sharks such as the Caribbean reef shark and the Blacktip shark.

7. Ball's Pyramid, Australia

Ball's Pyramid is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera. Ball's Pyramid is 20 kilometres (12 mi) southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean. It is 562 metres (1,844 ft) high, while measuring only 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) in length and 300 metres (980 ft) across, making it the tallest volcanic stack in the world. Ball's Pyramid is part of the Lord Howe Island Marine Park in Australia.

The pyramid was named after Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball who discovered it in 1788 at the same time he discovered Lord Howe Island. The first person to go ashore is believed to have been Henry Wilkinson in 1882, who was a geologist at the New South Wales Department of Mines. Climbing was banned in 1982 under amendments to the Lord Howe Island Act, and in 1986 all access to the island was banned by the Lord Howe Island Board. In 1990 the policy changed to allow some climbing under strict conditions, which in recent years has required an application to the relevant state Minister.

In 2001, a team of entomologists and conservationists landed on Balls Pyramid to chart its flora and fauna. To their surprise they rediscovered a population of the Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) living in an area of six by 30m (100ft), at a height of 100m (328ft) above the shoreline, under a single Melaleuca howeana shrub.

The bush is growing in a small crevice where water was seeping through cracks in the underlying rocks. This moisture supported relatively lush plant growth which had, over time, resulted in a build up of plant debris, several metres deep. The population was extremely small, only 24 individuals. Two pairs were brought to two Pacific zoos to breed new populations. On the unsuccessful 1964 climb, Dave Roots had brought back a photograph of the insect, which the Australian Museum told him they thought was extinct.

8. Malé, Maldives

Malé is the capital and most populous city in the Republic of Maldives. It is geographically located at the southern edge of North Malé Atoll (Kaafu Atoll). Malé island is heavily urbanized, with the built-up area taking up essentially its entire landmass.

Slightly less than one third of the nation's population lives in the capital city, and the population has increased from 20,000 people in 1987 to 100,000 people in 2006. Many, if not most, Maldivians and foreign workers in Maldives find themselves in occasional short term residence on the island since it is the only entry point to the nation and the centre of all administration and bureaucracy.

The Island of Malé is the fifth most densely populated island in the world, and it is the 168th most populous island in the world. Since there is no surrounding countryside, all infrastructure has to be located in the city itself. Water is provided from desalinated ground water; the water works pumps brackish water from 50-60m (164-197ft) deep wells in the city and desalinates that using reverse osmosis.

Electric power is generated in the city using diesel generators. Sewage is pumped unprocessed into the sea. Solid waste is transported to nearby islands, where it is used to fill in lagoons. The airport was built in this way, and currently the Thilafushi lagoon is being filled in. Many government buildings and agencies are located on the waterfront. Malé International Airport is on adjacent Hulhule Island which includes a seaplane base for internal transportation. Several land reclamation projects have expanded the harbour.

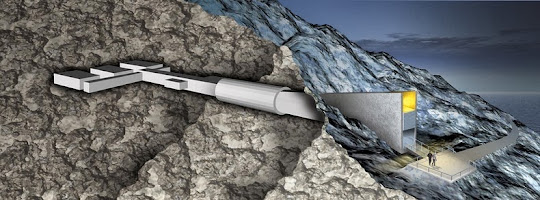

9. Atlantic Ocean Road, Norway

The Atlantic Ocean Road or the Atlantic Road is a 8.3-kilometer (5.2 mi) long section of County Road 64 that runs through an archipelago in Eide and Averøy in Møre og Romsdal, Norway. It passes by Hustadvika, an unsheltered part of the Norwegian Sea, connecting the island of Averøy with the mainland and Romsdalshalvøya peninsula. It runs between the villages of Kårvåg on Averøy and Vevang in Eida.

It is built on several small islands and skerries, which are connected by several causeways, viaducts and eight bridges - the most prominent being Storseisundet Bridge.

The road is preserved as a cultural heritage site and is classified as a National Tourist Route. It is a popular site to film automotive commercials, has been declared the world's best road trip, and been awarded the title as "Norwegian Construction of the Century". In 2009, the Atlantic Ocean Tunnel opened from Averøy to Kristiansund; together they form a second fixed link between Kristiansund and Molde.

10. Rock Islands, Palau

The Rock Islands of Palau are a small collection of limestone or coral uprises, ancient relics of coral reefs that violently surfaced to form Islands in Palau's Southern Lagoon, between Koror and Peleliu, and are now an incorporated part of Koror State. There are between 250 to 300 islands in the group according to different sources, with an aggregate area of 47 square kilometres (18 sq mi) and a height up to 207 metres (679 ft). They are a World Heritage Site since 2012.

The islands are for the most part uninhabited and are famous for their beaches, blue lagoons and the peculiar umbrella-like shapes of many of the islands themselves. The Rock Islands and the surrounding reefs make up Palau's popular tourist sites such as Blue Corner, Blue hole, German Channel, Ngermeaus Island and the famed Jellyfish Lake, one of the many Marine lakes in the Rock Islands that provides home and safety for several kinds of stingless jellyfish found only in Palau.

It is the most popular dive destination in Palau, and offers some of the best and most diverse dive sites on the planet. From wall diving to high current drift dives, from Manta Rays to sharkfeeds an from shallow and colorful lagoons to brilliantly decorated caves and overhangs.

Many of the islands' display a mushroom-like shape with a smaller base at the intertidal notch than what lies above it. The indentation comes from erosion and from the dense community of sponges, bivalves, chitons, snails, urchins and others that graze mostly on algae.

Source

READ MORE»

1. Meeting Place of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea at Eleuthera Island, Bahamas

Eleuthera is one of several islands that lies within the archipelago in The Bahamas, about 80km (50mi) east of the capital city Nassau. It is long – about 180km (112mi) – and thin - only about 1.6 km (1mi) wide in places. The light blue waters of the shallow Caribbean Sea on one side of the island stand out in stark contrast to the deep blue of the Atlantic Ocean thousands of feet in depth. One of the best places to see this extraordinary juxtaposition is at the Glass Window Bridge.

The Glass Window Bridge is about two miles east of Upper Bogue and joins Gregory Town and Lower Bogue at the narrowest point on the island. It is one of the few places on earth where you can compare the rich blue waters of the Atlantic Ocean on one side of the road and the calm turquoise-green waters of the Exuma Sound (Caribbean Sea) on the other side, separated by a strip of rock just 30 feet (10m) wide.

Over the natural rock bridge, a concrete bridge has been built that connects the northern and southern points of Eleuthera by a paved road. The Glass Window Bridge is one of the most visited places in the island.

For centuries, there was a natural stone bridge connection between north and south Eleuthera. Then in the 1940's, several hurricanes combined to destroy the land bridge and the concrete bridge was built as replacement. For decades, this bridge was kept functional by periodic repairs, but in 1992 and 1999 hurricane caused significant damage to the bridge. After the 1999 Hurricane Floyd, practically nothing of the original Glass Window Bridge remained. Although the bridge was repaired and Queen's Highway re-connected within a few months, the geography of Eleuthera was changed forever. Even after a decade, workers stay busy reinforcing the shoreline in order to re-pave the severely eroded asphalt.

One should take great care when visiting the Glass Window Bridge and the surrounding cliff areas. Rogue waves have been known to arrive unexpectedly and wash over the bridge and nearby cliffs. Since there are no immediate reefs along the ocean side to break up these rogue waves as they arrive, the waves can hit with great force and have been known to not only wash people out into the ocean, but vehicles as well.

Land is undergoing continuous erosion from the force of water that pounds from towering heights. On the left, approaching the bridge from the south, is a blow hole that spews water fantastically high, hinting at the power of the water beneath.

2. Meeting Place of the Baltic and North Sea, Denmark/Sweden

In the resort town of Skagen you can watch an amazing natural phenomenon. This city is the northernmost point of Denmark, where the Baltic and North Seas meet. The two opposing tides in this place can not merge because they have different densities. The area where the Baltic and the North Sea come into contact is quite shallow and so the contact face is relatively small. There is of course some mixing but it is quite minimal due to the difference of the density.

It is also helped by the fact that the Baltic is not tidal which keeps most of its water within the Baltic basin and this water is constantly being reduced in salinity by the rivers which drain into the Baltic. Were it not for that small opening into the North Sea the Baltic would be a giant fresh water lake. The contact area is a great sight to witness.

3. Horizontal Falls, Australia

The Horizontal Falls or Horizontal Waterfalls (nicknamed the "Horries") is the name given to a natural phenomenon on the coast of the Kimberley region in Western Australia.

Despite their name, the Horizontal Falls are a fast-moving tidal flow through two narrow, closely aligned gorges of the McLarty Range, located in Talbot Bay. The direction of the flow reverses with each change of tide. As tides in the Kimberley can reach 10 metres (33 ft), a peak tide gives rise to a significant difference in the sea level on either side of each gorge.

The northern, most seaward gorge is 20 metres (66 ft) wide and the southern, more inland gorge is 12 metres (40 ft). Above each of the gorges are natural reservoirs between six and eight kilometres (4-5 mi) long which fill and empty with seawater through the gorge openings. The inner gorge is also partly fed by fresh water from Poulton Creek.

4. The Deep Channel at the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system. It is composed of nearly 3,000 individual reefs and 920 islands stretching for over 2,650kilometres (1,620mi) over an area of approximately 345,000 square kilometres (133,100sqmi). The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, Australia.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's biggest single structure made by living organisms and can be seen from outer space. The reef structure is composed of and built by billions of tiny organisms, known as coral polyps. It supports an incredible diversity of life and was declared a World Heritage Site in 1981. It is one of the seven natural wonders of the world.

The Deep underwater channel from pictures above, separates Hook Reef from Hardy Reef, smaller reefs that belongs to Great Barrier Reef. It is often photographed from an airplanes and is a significant location for scuba divers.

5. 'Underwater Waterfall', Mauritius

Mauritius is an island nation officially called the Republic of Mauritius, or in French, République de Maurice, located in the Indian Ocean about 2,000 km (1,240mi) off the southeast coast of the African continent. A fascinating illusion can be found at the Southwestern tip of the island. When seen from the air, a runoff of sand and silt deposits makes the illusion of an underwater waterfall. The visually deceiving impression is absolutely breathtaking when seen from aerial shots. In fact, the illusion can even be seen on Google Maps.

Satellite views are dramatic, as an underwater current seemingly appears off the coastline of this tropical heaven. Viewed from other perspectives, the ocean appears to be a spectacular gamut of greens, blues, and whites, creating the false impression that it plummets down just like a raging waterfall. Causing the visual magic here is the sand, which is the fair-colored part of the water. The current caused by waves smashing against that specific part of the island causes the sand to be dispersed in a natural, waterfall-like manner of the receding waves’ downward pull. In a manner of speaking, it is in fact an underwater waterfall, but more akin to an hourglass, rather than a typical cascading water.

6. The Great Blue Hole, Belize

The Great Blue Hole is a large submarine sinkhole off the coast of Belize. It lies near the center of Lighthouse Reef, a small atoll 70 km (43 mi) from the mainland and Belize City. The hole is circular in shape, over 300 m (984 ft) across and 124 m (407 ft) deep. The Great Blue Hole is a part of the larger Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, a World Heritage Site of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

This is a popular spot amongst recreational scuba divers, who are lured by the opportunity to dive in crystal-clear water and meet several species of fish, including giant groupers, nurse sharks and several types of reef sharks such as the Caribbean reef shark and the Blacktip shark.

7. Ball's Pyramid, Australia

Ball's Pyramid is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera. Ball's Pyramid is 20 kilometres (12 mi) southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean. It is 562 metres (1,844 ft) high, while measuring only 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) in length and 300 metres (980 ft) across, making it the tallest volcanic stack in the world. Ball's Pyramid is part of the Lord Howe Island Marine Park in Australia.

The pyramid was named after Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball who discovered it in 1788 at the same time he discovered Lord Howe Island. The first person to go ashore is believed to have been Henry Wilkinson in 1882, who was a geologist at the New South Wales Department of Mines. Climbing was banned in 1982 under amendments to the Lord Howe Island Act, and in 1986 all access to the island was banned by the Lord Howe Island Board. In 1990 the policy changed to allow some climbing under strict conditions, which in recent years has required an application to the relevant state Minister.

In 2001, a team of entomologists and conservationists landed on Balls Pyramid to chart its flora and fauna. To their surprise they rediscovered a population of the Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) living in an area of six by 30m (100ft), at a height of 100m (328ft) above the shoreline, under a single Melaleuca howeana shrub.

The bush is growing in a small crevice where water was seeping through cracks in the underlying rocks. This moisture supported relatively lush plant growth which had, over time, resulted in a build up of plant debris, several metres deep. The population was extremely small, only 24 individuals. Two pairs were brought to two Pacific zoos to breed new populations. On the unsuccessful 1964 climb, Dave Roots had brought back a photograph of the insect, which the Australian Museum told him they thought was extinct.

8. Malé, Maldives

Malé is the capital and most populous city in the Republic of Maldives. It is geographically located at the southern edge of North Malé Atoll (Kaafu Atoll). Malé island is heavily urbanized, with the built-up area taking up essentially its entire landmass.

Slightly less than one third of the nation's population lives in the capital city, and the population has increased from 20,000 people in 1987 to 100,000 people in 2006. Many, if not most, Maldivians and foreign workers in Maldives find themselves in occasional short term residence on the island since it is the only entry point to the nation and the centre of all administration and bureaucracy.

The Island of Malé is the fifth most densely populated island in the world, and it is the 168th most populous island in the world. Since there is no surrounding countryside, all infrastructure has to be located in the city itself. Water is provided from desalinated ground water; the water works pumps brackish water from 50-60m (164-197ft) deep wells in the city and desalinates that using reverse osmosis.

Electric power is generated in the city using diesel generators. Sewage is pumped unprocessed into the sea. Solid waste is transported to nearby islands, where it is used to fill in lagoons. The airport was built in this way, and currently the Thilafushi lagoon is being filled in. Many government buildings and agencies are located on the waterfront. Malé International Airport is on adjacent Hulhule Island which includes a seaplane base for internal transportation. Several land reclamation projects have expanded the harbour.

9. Atlantic Ocean Road, Norway

The Atlantic Ocean Road or the Atlantic Road is a 8.3-kilometer (5.2 mi) long section of County Road 64 that runs through an archipelago in Eide and Averøy in Møre og Romsdal, Norway. It passes by Hustadvika, an unsheltered part of the Norwegian Sea, connecting the island of Averøy with the mainland and Romsdalshalvøya peninsula. It runs between the villages of Kårvåg on Averøy and Vevang in Eida.

It is built on several small islands and skerries, which are connected by several causeways, viaducts and eight bridges - the most prominent being Storseisundet Bridge.

The road is preserved as a cultural heritage site and is classified as a National Tourist Route. It is a popular site to film automotive commercials, has been declared the world's best road trip, and been awarded the title as "Norwegian Construction of the Century". In 2009, the Atlantic Ocean Tunnel opened from Averøy to Kristiansund; together they form a second fixed link between Kristiansund and Molde.

10. Rock Islands, Palau

The Rock Islands of Palau are a small collection of limestone or coral uprises, ancient relics of coral reefs that violently surfaced to form Islands in Palau's Southern Lagoon, between Koror and Peleliu, and are now an incorporated part of Koror State. There are between 250 to 300 islands in the group according to different sources, with an aggregate area of 47 square kilometres (18 sq mi) and a height up to 207 metres (679 ft). They are a World Heritage Site since 2012.

The islands are for the most part uninhabited and are famous for their beaches, blue lagoons and the peculiar umbrella-like shapes of many of the islands themselves. The Rock Islands and the surrounding reefs make up Palau's popular tourist sites such as Blue Corner, Blue hole, German Channel, Ngermeaus Island and the famed Jellyfish Lake, one of the many Marine lakes in the Rock Islands that provides home and safety for several kinds of stingless jellyfish found only in Palau.

It is the most popular dive destination in Palau, and offers some of the best and most diverse dive sites on the planet. From wall diving to high current drift dives, from Manta Rays to sharkfeeds an from shallow and colorful lagoons to brilliantly decorated caves and overhangs.

Many of the islands' display a mushroom-like shape with a smaller base at the intertidal notch than what lies above it. The indentation comes from erosion and from the dense community of sponges, bivalves, chitons, snails, urchins and others that graze mostly on algae.

Source